The First Great Monument of Islamic Art Is

What is Islam?

Islam is the youngest of the earth's great faiths, having developed in the 7th century C.E. The faith centers around the letters from God (Allah is the Arabic word for God) received by a prophet chosen Muhammad through an intermediary called the Angel Gabriel. A Muslim is a follower of Islam. Muslims believe that Islam is the merely true and original religion and it was attempted to be revealed by God previously in its true class through Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. However, through human fallacies the messages were distorted. The virtually contempo messages from God to the Prophet Muhammad succeeded in delivering the message to the people.Therefore, Islam is part of the Jewish and Christian tradition. You tin read about a few of the basic practices of Islam hither.

Much of Islamic art is functional: pottery, metalwork, buildings, etc. because of a prohibition against making realistic images of living creatures (animals and especially humans). This is primarily considering Islam believes that any representation of God'due south piece of work is imperfect, and is hence shameful. Every bit a result, Islamic art does not attempt to emulate/depict any living things. It goes even further according to the prophet Muhammad: artists who attempt to create realistic art (life-like paintings and sculptures for example) are trying to "create" life and will suffer severe punishments in hell for trying to be similar God.

Early on Islamic Art: The Caliphates (Political/Religious Dynasties)

The umbrella term "Islamic art" casts a pretty big shadow, covering several continents and more than a dozen centuries. So to make sense of information technology, we get-go have to get-go suspension information technology down into parts. One way is by medium—say, ceramics or architecture—merely this method of categorization would entail looking at works that span 3 continents. Geography is another means of organization, merely modern political boundaries rarely match the borders of past Islamic states.

A common solution is to consider instead, the historical caliphates (the states ruled by those who claimed legitimate Islamic rule) or dynasties. Though these distinctions are helpful, it is important to carry in mind that these are not discrete groups that produced ane detail style of artwork. Artists throughout the centuries have been affected by the exchange of goods and ideas and have been influenced by ane another.

Umayyad (661–750)

Map showing Islam expansion from 622 to 750

Four leaders, known as the Rightly Guided Caliphs, connected the spread of Islam immediately following the death of the Prophet. It was post-obit the death of the fourth caliph that Mu'awiya seized ability and established the Umayyad caliphate, the start Islamic dynasty. During this period, Damascus became the capital and the empire expanded West and East.

Dome of the Rock, 687, Jerusalem (photograph: Orientalist, CC BY 3.0)

The first years following the death of Muhammad were, of grade, formative for the faith and its artwork. The immediate needs of the organized religion included places to worship (mosques) and holy books (Korans) to convey the word of God. So, naturally, many of the first artistic projects included ornamented mosques where the faithful could get together and read Korans with cute calligraphy. Because Islam was still a very new religion, it had no artistic vocabulary of its ain, and its earliest work was heavily influenced by older styles in the region. Chief amidst these sources were the Coptic tradition of present-day Arab republic of egypt and Syria, with its scrolling vines and geometric motifs, Sassanian metalwork and crafts from what is now Iraq with their rhythmic, sometimes abstracted qualities, and naturalistic Byzantine mosaics depicting animals and plants.

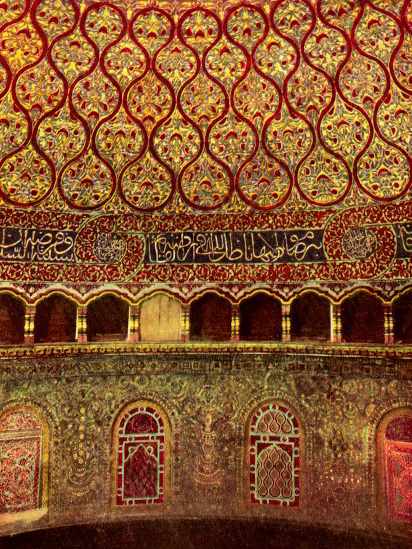

Interior of the base of the dome, Dome of the Rock

These elements tin can exist seen in the primeval significant work from the Umayyad catamenia, the nigh important of which is the Dome of the Stone in Jerusalem. This stunning monument incorporates Coptic, Sassanian, and Byzantine elements in its decorative programme and remains a masterpiece of Islamic compages to this twenty-four hour period.

Remarkably, just i generation after the religion'south inception, Islamic civilization had produced a magnificent, if singular, monument. While the Dome of the Stone is considered an influential piece of work, it bears footling resemblance to the multitude of mosques created throughout the remainder of the caliphate. It is important to bespeak out that the Dome of the Rock is not a mosque but a shrine commemorating an important event in the Islamic faith. A more mutual plan, based on the house of the Prophet, was used for the vast bulk of mosques throughout the Arab peninsula and the Maghreb. Perhaps the most remarkable of these is the Great Mosque of Córdoba (784-786) in Spain, which, like the Dome of the Stone, demonstrates an integration of the styles of the existing culture in which it was created.

Abbasid (750–1258)

The Abbasid revolution in the mid-8th century concluded the Umayyad dynasty, resulted in the massacre of the Umayyad caliphs (a unmarried caliph escaped to Kingdom of spain, prolonging Umayyad work after dynasty) and established the Abbasid dynasty in 750. The new caliphate shifted its attention e and established cultural and commercial capitals at Baghdad and Samarra.

Bowl, 9th century, Susa, Islamic republic of iran, Earthenware, metal lustre overglaze decoration, opaque glaze

The Umayyad dynasty produced little of what we would consider decorative arts (like pottery, glass, metalwork), merely under the Abbasid dynasty production of decorative stone, wood and ceramic objects flourished. Artisans in Samarra adult a new method for carving surfaces that immune for curved, vegetal forms (called arabesques) which became widely adopted. There were too developments in ceramic ornament. The apply of luster painting (which gives ceramic ware a metallic sheen) became pop in surrounding regions and was extensively used on tile for centuries. Overall, the Abbasid epoch was an important transitional period that disseminated styles and techniques to distant Islamic lands.

The Abbasid empire weakened with the establishment and growing power of semi-autonomous dynasties throughout the region, until Baghdad was finally overthrown in 1258. This dissolution signified not just the stop of a dynasty, but marked the last time that the Arab-Muslim empire would be united as one entity.

Mosque Compages

Mimar Sinan, courtyard of the Süleymaniye Mosque, İstanbul, 1558

From Indonesia to the United Kingdom, the mosque in its many forms is the quintessential Islamic building. The mosque, masjid in Arabic, is the Muslim gathering place for prayer.Masjid only means "place of prostration." Though almost of the v daily prayers prescribed in Islam can take place anywhere, all men are required to assemble together at the mosque for the Friday apex prayer.

Mosques are likewise used throughout the week for prayer, report, or simply as a place for rest and reflection. The main mosque of a city, used for the Friday communal prayer, is called a jami masjid, literally pregnant "Friday mosque," but it is also sometimes called a congregational mosque in English. The mode, layout, and decoration of a mosque tin tell us a lot nigh Islam in general, simply also about the flow and region in which the mosque was synthetic.

Diagram reconstruction of the Prophet's Firm, Medina, Saudi arabia

The dwelling house of the Prophet Muhammad is considered the first mosque. His firm, in Medina in modern-twenty-four hour period Saudi arabia, was a typical seventh-century Arabian mode house, with a large courtyard surrounded past long rooms supported by columns. This mode of mosque came to be known every bit a hypostyle mosque, meaning "many columns." Well-nigh mosques built in Arab lands utilized this style for centuries.

Common Features

The architecture of a mosque is shaped nearly strongly past the regional traditions of the time and identify where information technology was built. As a result, style, layout, and ornamentation tin can vary greatly. Nevertheless, because of the common function of the mosque as a place of congregational prayer, certain architectural features announced in mosques all over the world.

Sahn (Courtyard)

The most fundamental necessity of congregational mosque architecture is that it be able to hold the entire male population of a city or town (women are welcome to attend Friday prayers, but non required to practise and then). To that finish congregational mosques must have a big prayer hall. In many mosques this is adjoined to an open courtyard, chosen a sahn. Within the courtyard ane frequently finds a fountain, its waters both a welcome respite in hot lands, and important for the ablutions (ritual cleansing) done before prayer.

Mihrab and minbar, Mosque of Sultan Hassan, Cairo, 1356-63 (photograph: Dave Berkowitz, CC BY)

.jpg)

Mihrab, Bully Mosque of Cordoba, c. 786 (photo: Bongo Vongo, CC BY-SA)

Mihrab (Niche)

Another essential element of a mosque's compages is a mihrab—a niche in the wall that indicates the direction of Mecca, towards which all Muslims pray. Mecca is the metropolis in which the Prophet Muhammad was built-in, and the habitation of the most important Islamic shrine, the Kaaba. The direction of Mecca is called the qibla, so the wall in which the mihrab is set is called the qibla wall. No matter where a mosque is, its mihrab indicates the direction of Mecca (or every bit nigh that direction equally science and geography were able to place it). Therefore, a mihrab in India will be to the west, while a one in Egypt will exist to the east. A mihrab is usually a relatively shallow niche, every bit in the example from Egypt, in a higher place. In the example from Espana, shown correct, themihrab's niche takes the class of a pocket-sized room, this is more rare.

Minbar (Pulpit)

Mimar Sinan, Minaret, Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul, 1558

The minbar is often located on the qibla wall to the correct of the mihrab. A minbar is a pulpit from which the Friday sermon is delivered. Unproblematic minbars consist of a brusk flight of stairs, only more elaborate examples may enclose the stairway with ornate panels, doors, and a covered pulpit at the top.

Minaret (Belfry)

1 of the about visible aspects of mosque architecture is the minaret, a belfry next or attached to a mosque, from which the call to prayer is announced. Minarets take many different forms—from the famous spiral minaret of Samarra, to the alpine, pencil minarets of Ottoman Turkey. Not solely functional in nature, the minaret serves every bit a powerful visual reminder of the presence of Islam.

Qubba (Dome)

Near mosques also feature one or more domes, called qubba in Arabic. While not a ritual requirement like the mihrab, a dome does possess significance within the mosque—as a symbolic representation of the vault of heaven. The interior decoration of a dome ofttimes emphasizes this symbolism, using intricate geometric, stellate, or vegetal motifs to create breathtaking patterns meant to awe and inspire. Some mosque types incorporate multiple domes into their architecture (equally in the Ottoman Süleymaniye Mosque pictured at the top of the page), while others only feature one. In mosques with just a single dome, it is invariably establish surmounting the qibla wall, the holiest section of the mosque. The Cracking Mosque of Kairouan, in Tunisia (non pictured) has 3 domes: one atop the minaret, one above the entrance to the prayer hall, and one above the qibla wall.

Mosque lamp, 14th century, Egypt or Syria, blown glass, enamel, gilding, 31.8 ten 23.ii cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Considering information technology is the directional focus of prayer, the qibla wall, with its mihrab and minbar, is often the most ornately decorated area of a mosque. The rich decoration of the qibla wall is apparent in this paradigm of the mihrab and minbar of the Mosque of Sultan Hasan in Cairo, Egypt (see paradigm higher on the page).

Furnishings

At that place are other decorative elements common to nigh mosques. For instance, a big calligraphic frieze or a cartouche with a prominent inscription ofttimes appears above the mihrab. In most cases the calligraphic inscriptions are quotations from the Qur'an, and oft include the engagement of the edifice's dedication and the name of the patron. Another of import feature of mosque decoration are hanging lamps, also visible in the photo of the Sultan Hasan mosque. Light is an essential feature for mosques, since the first and concluding daily prayers occur before the sun rises and after the sun sets. Before electricity, mosques were illuminated with oil lamps. Hundreds of such lamps hung inside a mosque would create a glittering spectacle, with soft calorie-free emanating from each, highlighting the calligraphy and other decorations on the lamps' surfaces. Although not a permanent function of a mosque building, lamps, along with other furnishings like carpets, formed a meaning—though ephemeral—aspect of mosque architecture.

Other Features

Most historical mosques are not stand-solitary buildings. Many incorporated charitable institutions like soup kitchens, hospitals, and schools. Some mosque patrons also chose to include their own mausoleum as part of their mosque complex. The endowment of charitable institutions is an important aspect of Islamic civilization, due in part to the third pillar of Islam, which calls for Muslims to donate a portion of their income to the poor.

Mihrab, 1354–55, just after the Ilkhanid period, Madrasa Imami, Isfahan, Iran, polychrome glazed tiles, 343.1 10 288.vii cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The commissioning of a mosque would be seen every bit a pious act on the part of a ruler or other wealthy patron, and the names of patrons are usually included in the calligraphic ornament of mosques. Such inscriptions also often praise the piety and generosity of the patron. For instance, the mihrab now at the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, bears the inscription:

And he [the Prophet], blessings and peace be upon him, said: "Whoever builds a mosque for God, even the size of a sand-bickering nest, based on piety, [God will build for him a palace in Paradise]."

The patronage of mosques was not only a charitable human activity therefore, but also, like architectural patronage in all cultures, an opportunity for cocky-promotion. The social services attached the mosques of the Ottoman sultans are some of the most extensive of their type. In Ottoman Turkey the complex surrounding a mosque is called a kulliye. The kulliye of the Mosque of Sultan Suleyman, in Istanbul, is a fine example of this miracle, comprising a soup kitchen, a hospital, several schools, public baths, and a caravanserai (like to a hostel for travelers). The complex also includes two mausoleums for Sultan Suleyman and his family members.

Kulliyesi (view of kitchens and caravanserai), Istanbul

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-sac-artappreciation/chapter/reading-arts-of-the-islamic-world-the-early-period/

Postar um comentário for "The First Great Monument of Islamic Art Is"